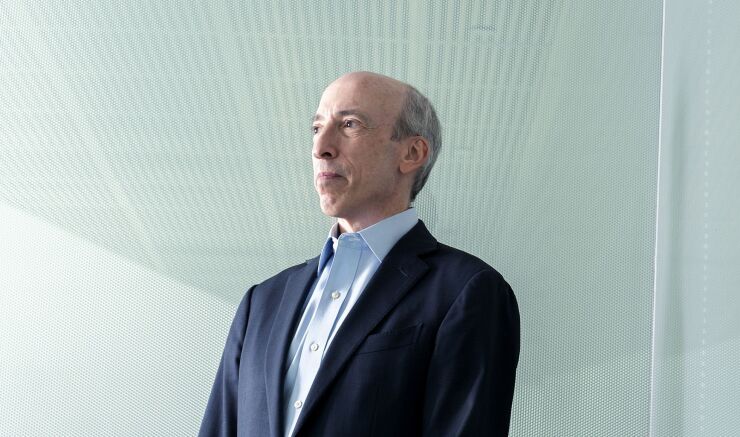

Gary Gensler is taking on the world.

The head of the Securities and Exchange Commission wants to light up the opaque world of private capital. He has already promised this year a closer look at crypto, online brokers like Robinhood and green investment funds in what has been called an “Everything Crackdown.”

A thorough examination of private capital is long overdue. It has seen explosive growth since the crisis of 2008. The modern buyout business has taken a material chunk of the economy out of the sunlight of public markets. For example, companies owned by KKR & Co. employ 820,000 people globally, which would make it one of America’s largest employers, equivalent to more than three JPMorgan Chase’s. Even after the biggest year for buyouts since 2007, private-equity firms still have about $1 trillion to plow into deals.

Gensler, a Democrat appointed by President Joe Biden this year to chair the regulator, got a reputation as a serious reformer in his stint at the Commodity Futures Trading Commission immediately after the 2008 financial crisis. He listed some of the questions he wants answered about private capital and hedge funds in a speech to the biggest investors in the field last week.

In private equity, the focus is on returns, conflicts of interest and, most of all, the complex layering of fees and expenses that its partners charge their companies and investors. The SEC’s own compliance inspections unit has raised the alarm over investors being overcharged for expenses they shouldn’t pay – even investment managers’ travel and entertainment.

“Hundreds of billions of dollars in fees and expenses are standing between investors and businesses,” Gensler said.

His audience, the Institutional Limited Partners Association, had already appealed for his help. The group sent a letter to the SEC in October seeking action to force private fund managers and their affiliates to report all direct and indirect fees and expenses.

This isn’t just about the straight management and performance fees — as high as they already are. Gensler estimated those might add up to 3%-4% of assets every year. On $4.7 trillion of assets, that’s roughly $140 billion to $190 billion. Every. Year.

No, beyond those, Gensler also listed all sorts of other expenses loaded onto the companies that private-equity firms own and that investors may or may not end up paying. These include consultancy and monitoring fees — which really sound like part of just doing your job as the manager — as well as advisory fees, service fees and directors’ fees.

Sometimes the firms promise to deduct these from the straight management fees and then sometimes they don’t actually do that, as the SEC’s compliance inspection unit reported last year.

The largest private-equity groups, like Apollo Global Management, KKR and many others, house their own investment-banking units, lending and capital markets arms or business-services divisions.

This helps them capture more of the revenue their dealmaking generates, such firms say. The question investors are asking is whether it is being captured on their behalf or more for the benefit of the firms and their partners. We don’t know.

As private equity moves further into the territory of traditional banks and insurers, sharper regulation and monitoring to protect financial stability should be inevitable. Industry leaders are in denial about this, thinking that either it won’t happen or they can pay their way out of it through lobbying, according to a senior investment banker who deals regularly with private equity.

Despite all their power and scale, many people are starting to think that perhaps returns aren’t that hot anyway. Comparing private-equity funds’ returns to other investments like the stock market is no simple matter. Amazingly, even with thousands of hours of academic and industry research applied to the question, uncertainty remains.

With ordinary mutual funds, debates on fees and performance draw on a great deal of knowledge and information, Gensler said. “In contrast, basic facts about private funds are not as readily available — not only to the public, but even to the investors themselves.”

It’s not just scrappy academics questioning returns. Industry consultants at Bain & Co using one popular method last year showed that over the past decade, private equity with all its heavy borrowing and active management returned about the same as the S&P 500.

Many pension funds simply don’t know what they are really getting, according to former banker Jeffrey Hooke, senior lecturer in finance at Johns Hopkins Carey Business School. His new book, “The Myth of Private Equity,” delves into the asymmetry of incentives and information that have fed the industry’s growth. He is gloomy on the chances of reform. “The momentum behind the industry is just too strong and it’s got so much money that it’s too late,” he told me.

The SEC and others are worried about the power private capital holds over workers’ pay and rights as well as the returns for their pension funds. The growth of private capital means “a burgeoning portion of the U.S. economy itself is going dark,” SEC Commissioner Allison Herren Lee said in a recent speech.

This huge industry delivers stellar returns to a few hundred people in its top jobs, but it is far from clear that most funds do much for anyone else. If there is real value in private equity, the industry should welcome Gensler’s attention, open itself up to greater scrutiny and show us. Time to turn on the lights.