When Jamie Dimon, the head of America’s largest bank, says the U.S. economy is in jeopardy, Federal Reserve policy makers and elected officials ought to take notice.

This detail was tucked away in a Wall Street Journal

Dimon, of course, is hardly the first billionaire to bemoan the historically wide gap in the U.S. between rich and poor. Ray Dalio, founder of Bridgewater Associates, has

It’s easy to dismiss all this as cheap talk from those who benefited the most from the current system. But there’s only so much even the biggest hedge fund or largest U.S. bank can do to address these persistent problems. The power to narrow the yawning gaps in the world’s largest economy begins and ends in the walls of Congress. Unfortunately, for more than a decade, lawmakers have ceded much of that responsibility to the Fed, an institution that is particularly ill-equipped to address wealth inequality.

When I ask investors what they’ve learned in 2020, the answer is almost always the same: Don’t ever doubt how far the Fed is willing and able to go during periods of crisis. It added $3 trillion to its balance sheet in what seemed like a flash. It purchased corporate-bond ETFs, backstopped the municipal-debt market and injected enough confidence and liquidity into the financial system to lift the prices of just about all assets. As a result, U.S. household net worth reached an

So perhaps there’s another equally important takeaway from 2020: For all the central bank’s plaudits, its one kryptonite remains the same, whether in good economic times or bad. It’s powerless to stop the wealth gap in America from growing wider.

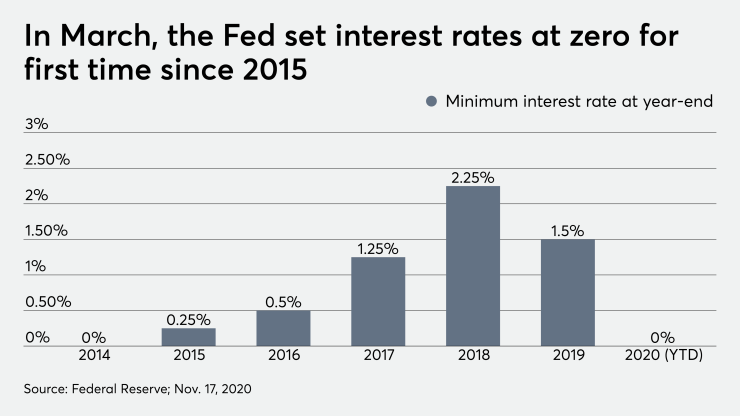

The reason is straightforward: At its core, the Fed sets the level of interest rates in the economy. If interest rates are low, as they are now, that props up the value of stocks and other risky assets, which are

That last part is the context that many Fed critics seem to miss. During a year like 2020, when stock markets raced to record highs even as many workers lost their jobs and small businesses folded, it’s tempting to paint the central bank as a villain; an institution always looking out for

Instead, those in search of a foe should focus on Congress.

Yes, lawmakers swiftly passed the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act early in 2020, which provided much-needed relief to many of those hit hardest by the pandemic. But over the course of at least the last decade, that sort of legislation has proved to be the exception rather than the norm. More typical was the excruciating back-and-forth over another round of fiscal aid that lasted for months.

The CARES Act showed how fiscal policy can chip away directly at wealth inequality. From March 31 through Sept. 30, the overall wealth of Americans in the bottom half increased by more than 20%, the largest two-quarter jump since late 2013. It was also a bigger boost than any of the other groups tracked by the Fed. Wealth rose 7.9% for those in the 50% to 90% tier, 10.3% in the 90% to 99% range and 15% for the top 1%. The top 10% now have roughly 34 times the wealth of the bottom half, which, while high on a historical basis, is also the lowest ratio since mid-2007, just before the longest recession since the Great Depression.

Now that the U.S. is five months into the COVID crisis a new victim is emerging. Caught between small businesses furloughing their staff landlords needing to collect rent are millions of hourly workers.

In that 13-year span, Congress has rarely been so focused on policies that support the most vulnerable Americans. Earlier in President Donald Trump’s term, Republicans passed a tax cut that

Some on Wall Street are optimistic that the COVID-19 pandemic has changed the thinking in Washington around fiscal stimulus. “We see no political appetite for fiscal austerity, even as debt ratios hit historic highs globally. The politics of inequality will likely keep deficit spending high,” according to the 2021 global outlook from the BlackRock Investment Institute. “A post-pandemic recovery requires fiscal stimulus beyond the fiscal life preserver,” strategists at Citigroup wrote. “Without fiscal easing, when the pandemic is brought under control for good, the risk remains for rising inequalities and diminished prospects for living standards.”

Yet there are ample reasons to be skeptical. For one, even after Trump demanded $2,000 stimulus checks, a vast majority of House Republicans balked and prospects are

“Monetary policy cannot change the distribution of wealth, monetary policy cannot get the stimulus to the right places today — it has to be fiscal,” Rick Rieder, BlackRock’s CIO of global fixed income, told me in an interview. When it comes to steering the economy, “Jay Powell will be the co-pilot and the pilot will be Janet Yellen. Because whether its tax redistribution or creating more employment, it has to come through fiscal. Monetary has done virtually everything it can do.”

As one example, Rieder points to the

Rieder

Channel money to the right places. Improve access to high-quality education and affordable housing. And once the pandemic has passed, perhaps even raise taxes on wealthier Americans after years of financial-market gains. These are all things elected officials can do and the Fed can’t.

I

By contrast, the path ahead is fairly simple for the Fed: It will keep interest rates pinned near zero until the economy approaches full employment and inflation averages 2%. That will be the policy regardless of whether wealth inequality grows even more extreme or reverses the long-term trend.

So in some ways 2020 taught us that the Fed is powerful — except in the area that Dimon and others are warning about.