There’s a showdown looming between financial advisors and the custodians that safeguard their clients’ money. It’s been brewing for some time, and the

Retail investors know Schwab as a discount broker, but it’s also a custodian for financial advisors who break away from banks, insurance companies and other financial firms, or set up shop on their own. Those advisors need someone to house client accounts and execute trades, and firms such as Schwab, Fidelity Investments, Bank of New York Mellon and TD Ameritrade are popular choices. (My asset-management firm works with Schwab and TD Ameritrade.)

It was a blissful union. Clients paid financial advisors a fee for constructing portfolios and financial planning, typically a percentage of assets under management, and custodians collected interest on clients’ cash and margin, distribution fees from mutual funds and, of course, commissions on trades. Lately, though, the relationship between advisors and custodians has become strained. While advisors continue to collect their fees, custodians are increasingly under pressure.

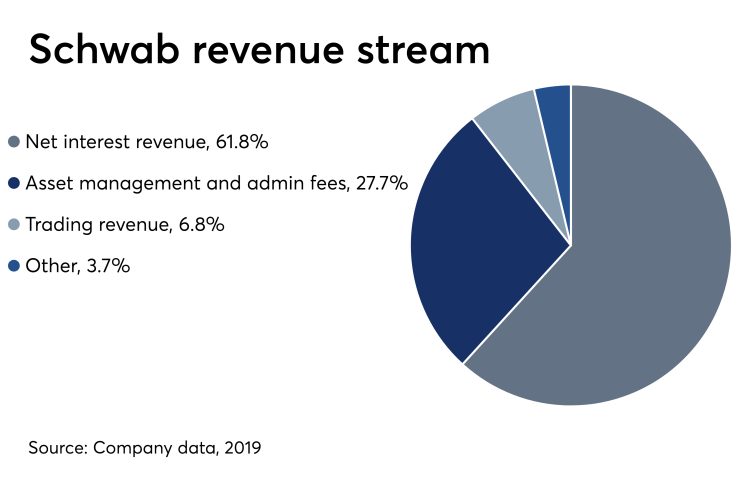

Roughly 40% of Schwab’s revenue last year came from proprietary mutual funds and ETFs, third-party mutual funds, commissions and – importantly – advisory fees. The value of all but the latter is now zero or trending in that direction. The other 60% of Schwab’s revenue, which is interest income primarily from margin loans, bank loans and fixed-income investments, isn’t likely to make up the difference. Schwab can only boost interest revenue by gathering more assets or praying for higher interest rates. Few expect rates to rise any time soon, and Schwab’s competitors are now offering free trades of their own, so there’s little reason for investors to flock to the broker.

As custodian-brokers raced to the bottom on fund fees and commissions, advisory fees have remained remarkably resilient. The average financial advisor continues to

It may also explain why clients are sticking with advisors despite growing competition from automated investing platforms that typically charge lower advisory fees, and in Schwab’s case, no fee (although Schwab makes money on its robo-advisor through proprietary ETFs and interest on cash balances). Clients may eventually feel comfortable handing their money to the bots, but most still seem to value proximity to human advisors.

The predictable result is that custodians, and even some mutual fund companies, are keen on getting closer to clients. Schwab, Fidelity and Vanguard Group have all made a big push into the advisory business in recent years. While hard numbers are hard to track down, Kitces estimates that those firms now account for “a material slice of the overall market for financial advice and a huge portion of the cumulative growth of advisory assets over the last four years.”

Custodians are likely to win. They have the expertise to navigate the dizzying array of mutual funds and ETFs sold to investors, plus the size and reach to undercut advisors’ fees and the resources to build technology advisors can only dream about. That doesn’t mean independent financial advisors will disappear, but many won’t survive the onslaught, and those who do can expect a pay cut.

—Bloomberg News, By: Nir Kaissar