Three of the world’s largest asset managers have been pushing back against claims they have too much influence over American companies. New data about the voting patterns at the fund houses could give critics more ammunition.

The Big Three index fund companies — BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street — vote the shares in their fund portfolios by following the house view, which means at least 75% of an asset manager’s funds voted the same way, on environmental and social issues.

This is the conclusion from a Morningstar analysis of 177 separate proposals related to sustainability and social issues from the 2019 proxy season. (The analysis excluded funds geared specifically toward sustainability to focus on how the rest of the funds vote.)

The data show that funds owned by the three largest index-fund firms voted in lockstep on all 177 proposals, revealing the growing sway they have in board rooms and adding to the increased antitrust and corporate governance concerns by academics and activists. Some contend that the fund companies’ ability to weigh in with more informed opinions is a positive for corporate governance.

-

"It's going to become increasingly more important for financial professionals to understand the potential benefits of sustainable investing," an exec says.

December 10 -

Many firms are modifying their ETFs’ existing mandates to be ESG-oriented without forcing investors to sell — and thus avoiding a tax bite.

February 12 -

The green investing movement has totaled at least $30.7 trillion of funds held in sustainable or green investments in 2018, up 34% from 2016, data show.

January 30

Other asset-management companies showed more variance in their voting practices. At Invesco, for example, on 76 of the 177 resolutions at least one fund voted at odds with the rest. On 10 of the proposals, fewer than three-quarters of the funds voted the same way.

At Pimco, at least one fund broke from the house consensus in 12 of the 149 proposals where it cast votes, according to Morningstar data.

The assets and influence of the Big Three have ballooned as investors have poured money into the benchmark-tracking funds they offer. Combined, they manage almost $16 trillion in assets. Bloomberg data show that they own 22% of the average company in the S&P 500.

Charles Munger, the Berkshire Hathaway vice chairman and Warren Buffett confidant, has joined the cavalcade of critics. “The voting power of the index funds is a sleeping giant,” said Munger. “If the giant wakes up, we don’t know what’s going to happen.”

HEATED DEBATE

The firms’ rise has prompted a heated debate, resulting in the FTC last month

Some of the studies assert that common ownership is one reason why the U.S. has seen more mergers, higher prices, less investment and reduced competition among rivals, all of which helps boost corporate profits — and index-fund returns.

Of the Big Three, two have said they may consider changing — possibly with a regulatory nudge — how they exert their power over U.S. boardrooms.

“It’s not surprising” that changing voting practices “is a topic of early stage discussion at a number of managers,” said Brian McCabe, a partner in the asset management group at law firm Ropes & Gray. “No one wants to be caught flat-footed.”

CONSIDERING OPTIONS

One option under consideration would involve dispersing voting power by making individual fund managers vote the shares in their portfolios, rather than the parent fund company voting the aggregated shares.

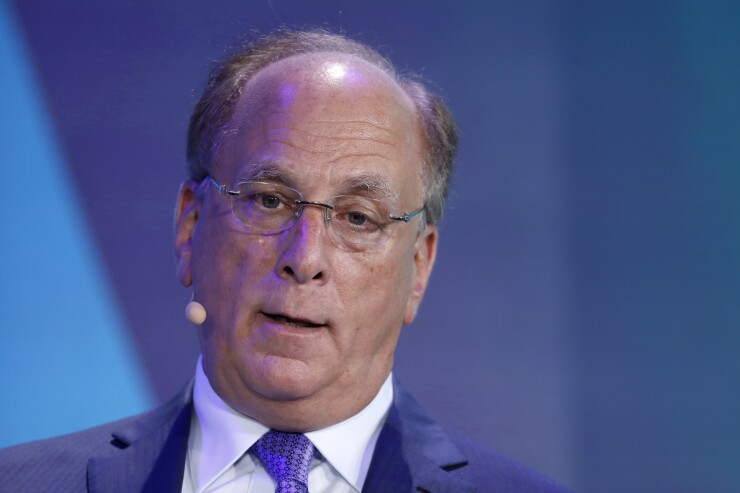

BlackRock CEO Larry Fink and State Street CEO Ron O’Hanley have said they would consider pushing voting power down that way.

Fink said it’s an adjustment the firm could enact relatively quickly. “If there is a societal view that there’s too much power rested on these few companies, then we could find a solution to mitigate that risk,” he said in an

In a recent

BlackRock on Wednesday said Barbara Novick, the firm’s vice chairman and co-founder who spearheaded opposition to common ownership criticisms, is stepping down after more than three decades at the company.

State Street’s O’Hanley

Neither company nor CEO would comment beyond their public remarks. Vanguard, which hasn’t said whether it’s considering changes in voting practices, declined to comment.

Broad-basket commodity sector funds, as well as those long on oil, natural gas and precious metals, accounted for more than half of the laggards.

Some common-ownership critics like the voting-dispersal idea. “The easiest thing to do,” said Einer Elhauge, a Harvard Law School professor who has studied the issue, “would be to stop voting at the fund family level.” If firms transferred voting power to individual fund managers — who then vote only to maximize the value of the funds they oversee — it could help address the risks of common shareholding, he said.

How this would work logistically is another matter. Proxy voting is a gargantuan task for the index-fund firms. In the U.S. alone, they must cast votes for about 28,000 CEOs and board directors. They also must consider thousands of other proposals, ranging from approving auditors to asking for greenhouse-gas emissions reports.

STEWARDSHIP ROLE

BlackRock has a team of 47 people in seven locations who interact with portfolio companies on governance matters. In the year ended June 30, 2019, these so-called stewards met with 1,458 companies.

If portfolio managers had to decide how to vote on multiple proposals at thousands of companies, they might not have much incentive to deviate from the recommendations of the stewardship team, effectively continuing current practice. In the end, it’s not clear that dispersing voting power would achieve the outcome the critics want.

Jackie Cook, the Morningstar director of sustainability stewardship research who ran the analysis on voting records, said the current model works because the biggest fund firms have the resources to invest in stewardship teams that focus on sustainability.

“Those people have been specifically hired for their expertise,” Cook said. “It’s really too much to expect an individual fund manager to have knowledge of all of these issues.”

Environmental and other activists, meanwhile, want to push the fund houses in the other direction — to use their voices more strongly. They complain that the fund houses don’t press portfolio companies enough to reduce carbon emissions, lower executive pay, address inequality or pursue other reforms that might not increase profit but that might be helpful to society at large.

“What we actually need to see right now is a level of responsible voting,” said Eli Kasargod-Staub, executive director of Majority Action, a nonprofit group that presses investors on climate action. “The antitrust arguments are legitimate concerns. It’s hard to see exactly what the right answer is on the policy. Fracturing their voting power I don’t think will get us there.” — Additional reporting by Katherine Chiglinsky