Late last year, The Wall Street Journal wrote a piece called “

“We strongly disagree with the conclusions it reached about the efficacy of our ratings,”

I have long relied on Morningstar data and analysis to help clients, so the article was food for thought: Have I, too, been duped by a mirage?

The article examined the famous Morningstar five-star rating system, which categorizes funds and then looks at past performance within each category. The top funds get a five-star rating while the worst performing funds get a one-star rating. It found past performance did not persist. About 10% of funds get the coveted five-star rating but, over the next five years, only 12% of funds performed at that same five-star level consistently.

In fact, it found that 10% of those former five-star funds performed at the one-star level. That’s about what one would expect by random selection. The article pointed to investors placing reliance on the star rating only to get atrocious returns going forward.

The article didn’t ignore Morningstar’s newer forward-looking rating system. This system assigns funds one of five ratings: gold, silver, bronze, neutral and negative. It pointed out that of the funds reviewed in this new system, the majority had very strong ratings. The Wall Street Journal found that, over the next five years, the average gold-medal fund performed at a 3.4-star level while a silver medal fund performed at a 3.3-star level.

Finally, the WSJ brought attention to some potential conflicts of interest. Morningstar charges fees to mutual fund companies for data and to be able to use its name in star ratings. Furthermore, Morningstar is launching nine mutual funds of its own — meaning a firm that rates mutual funds will also now rate its own funds.

Though I found nothing in The Wall Street Journal article to be inaccurate, I also found very little that was new. This is particularly true when hearing “past performance is not indicative of future performance,” and the star rating definitely reflects past performance. In fact, since at least 2010, Morningstar has said that

-

The new tool will incorporate analysts’ past decisions and data, and extend their approach to funds not currently covered.

March 5 -

Winners were from Fidelity, Causeway, T. Rowe Price and Prudential.

January 24 -

Research into the point system for ranking funds questions whether the metric is valid in gauging future performance.

November 7

“One key concern I have with the WSJ is the scope. It explores the efficacy of the star rating as a metric to select funds, when that was never its intended purpose,” says David Blanchett, head of retirement research at Morningstar Investment Management. “What the WSJ should have been exploring is our newer comprehensive metric of fund quality, called the Morningstar Analyst Rating, created in 2011, where preliminary

Even so, the star rating may have been a better predictor than The Wall Street Journal gave it credit for. According to Morningstar, 56% of the one-star funds went out of business in the next five years while only 9% of five-star funds did so. The funds that went out of business presumably were not high performers.

Is it Morningstar’s responsibility that some advisors rely too much, or maybe even completely, on its ratings? Perhaps. But the ultimate responsibility falls to those, especially advisors, who place too much reliance historic measures of performance.

Once upon a time, mutual funds touted their performance relative to the stock market. In fact, many compared their total returns to the raw S&P 500 index, stripped of dividends. This, of course, presented two distortions:

- Riskier small-cap value funds, which have greater growth as compensation for taking on more risk, looked as if their managers were brilliant.

- Most managers appeared to best the market by comparing their total returns to part of the market’s returns (raw S&P 500 index).

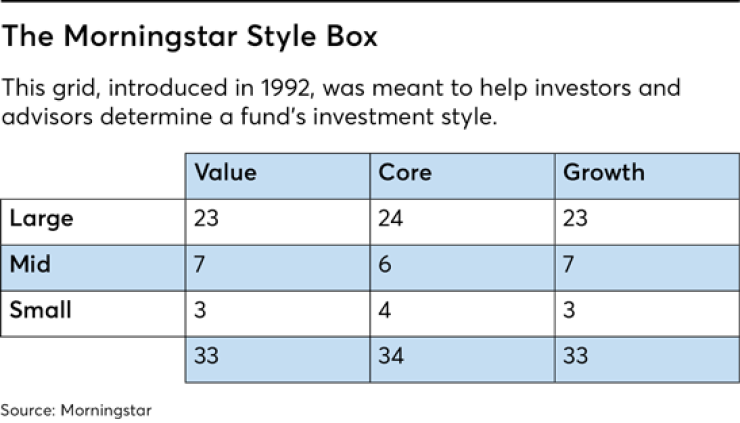

So back in 1992, one of the earliest Morningstar employees, Don Phillips, invented the famous

That style box was quite helpful for investors and advisors. But I suspect The Wall Street Journal data would have been far more flattering to Morningstar had they just kept one universe of domestic and international stocks. That is to say, the riskier funds would tend to perform better over longer periods of time and thus performance would be more predictable. Lost, however, would have been the risk-adjusted performance.

Morningstar also developed a similar nine-style box for bonds that looked at credit quality and duration. No longer could a long-term junk bond fund be compared to the overall bond market, which happens to be predominantly issued by the U.S. government and its agencies.

I suspect The Wall Street Journal data would have been far more flattering to Morningstar had they just kept one universe of domestic and international stocks.

Finally, in 2011, Morningstar came out with the forward-looking rating system mentioned earlier. The Wall Street Journal was correct that only 26% of funds are rated. Yet, according to Morningstar, that represents about 77% of mutual fund assets. And, quite frankly, gold and silver funds averaging 3.4 and 3.3-star historic performance isn’t bad in my book.

Does Morningstar care how its data is used?

I’ve had a few experiences in looking at false conclusions based on Morningstar data. Here are three.

First, I once examined an

Next, in 2016 the Journal of Financial Planning published the conclusions of an academic study that claimed to use Morningstar data to prove

Finally, over the past couple of years, I’ve frequently heard that bond indexing has failed. Morningstar data is cited in this conclusion by noting the bond index funds following the Barclays Aggregate Bond Index (such as Vanguard Total Bond and iShares Aggregate Bond) had underperformed their peers over the past 10 years.

Morningstar was quick to point out that its methodology for assigning peer groups is imperfect. It turns out that the peer group, while predominantly investment grade, had much lower credit quality and noted its data

So how should advisors use Morningstar to help clients?

I place virtually zero weighting on Morningstar’s historic five-star ratings, but I do use Morningstar historic data to look at how a portfolio from a new client has performed against the total returns of broad index funds, similarly weighted.

Using Morningstar to summarize the entire portfolio on factors like asset class allocation, style, sector, turnover and fees allows me to assess the portfolio against goals and assess how much risk (compensated and uncompensated) the portfolio is taking. Compensated risk is measured by broad asset classes (stocks vs. bonds, for example) while uncompensated risk includes betting on sectors, industries or a small number of underlying stocks.

Next, I look at the costs and turnovers within these funds to determine whether we should hold or sell each fund in developing a new portfolio. That is to say, the costs and turnover need to be weighed against the tax ramifications of selling.

Then, in selecting new funds, Morningstar data shows me what’s inside each fund. The data allows me to pick the lowest-cost, most tax-efficient funds that offer the broadest coverage in the desired asset class.

When I build a portfolio from scratch, with no tax legacy, the three funds that represent the core of the portfolio are the Vanguard Total U.S. Stock Index Fund (VTSAX), the Vanguard Total International Stock Index Fund (VTIAX), and the Vanguard Total Bond Index Fund (VBTLX). Let’s look at the mediocre historic Morningstar ratings for the admiral-share class of these funds.

Of course, it’s virtually impossible for a fund that owns an entire market to be a top performing 5-star fund. While I’ve been using these funds long before Morningstar came out with its

- People: Who is running the fund

- Process: How the fund selects its holdings

- Parent: Evaluation of the parent company, including its stewardship rating

- Performance: Risk-adjusted performance within category

- Price: The expense ratio relative to other funds with similar investment objectives.

Lest I be branded a Morningstar cheerleader, let me make it perfectly clear — I don’t agree with everything. First, my biggest criticism, not mentioned in The Wall Street Journal article, is that the

Second, I agree with The Wall Street Journal that coming out with its own mutual funds is a conflict of interest. Morningstar stated to me that this is both in a separate subsidiary and that it will not be rating its own funds in the forward-looking ratings. These new funds, however, will be eligible for the star ratings once enough performance history is available. The appearance of a conflict raises red flags.

In the end, I still believe Morningstar is a useful tool for advisors. The company has long been an advocate for indexing and low fees because the data demonstrated its benefits for investors. That’s academic integrity in my book.

Used properly, Morningstar’s data can help advisors analyze current portfolios and construct new ones. That creates value for our clients.