From the moment the Roth IRA was created in the late 1990s, it has been a popular vehicle to generate future tax-free growth and income, whether by contributing to the account on an ongoing basis, or even doing a Roth conversion of an existing IRA or other pre-tax retirement account.

Yet the caveat is that the decision to contribute or convert to a Roth IRA incurs an immediate tax liability. And in the extreme, a large Roth conversion can generate so much taxable income that it actually drives up the IRA owner's tax bracket to the point that the transaction becomes wealth destructive.

Fortunately, though, the decision to do a Roth conversion doesn't have to be "all or none" – and in fact, not only is a partial Roth conversion permitted, but in practice it's often the optimal strategy, allowing retirement account owners to convert just enough to fill the lower tax brackets, without causing too much income that would trigger the top tax brackets.

In fact, the Roth recharacterization rules make it feasible to precisely fill the bottom tax brackets, but not a dollar more, by converting more than enough to fill the lower tax brackets each year, and then doing a partial recharacterization to back into the optimal partial Roth conversion amount after the year is over.

HOW TO DO IT

Notably, though, while the Roth conversion rules are often discussed as though an entire IRA or other pre-tax retirement account might be converted, the reality is that

Similarly, under the Roth recharacterization rules of

The fundamental point: Roth conversions really don't have to be an all-or-none transaction, and can either be done as a partial Roth conversion on a prospective basis, or partially recharacterized after the fact to create the same result. And in practice, doing a partial Roth conversion – or rather, a series of them – is often the best way to maximize the long-term value of a pre-tax retirement account.

FILLING THE LOWER BRACKETS

The virtue of doing a Roth conversion is that once converted, subsequent growth in the account can be spent tax-free as a qualified Roth distribution in the future. The caveat, of course, is that doing the Roth conversion forces the value of the account to be reported as income today, triggering an immediate tax liability. To come out ahead,

Yet given that a Roth conversion itself is income for tax purposes, a large single-year Roth conversion can become self-defeating; because tax brackets are progressive (the higher the income, the higher the tax rate), if enough dollars are converted at once, so much income is created that the taxpayer is driven into the top tax brackets. Which ironically means there really is such thing as doing too much of a Roth conversion, where the effort to create a large tax-free account all at once with a huge conversion drives up tax rates to the point of making it less desirable (or outright destructive) in the long run to have done so.

Example 1: Jeremy and Linda's current combined income after deductions is $60,000, putting them in the 15% tax bracket. They have a $500,000 IRA that they are considering whether to convert to a Roth IRA to avoid

In this context, the partial Roth conversion suddenly becomes appealing. Converting the entire account may drive the couple's marginal tax rate into the top 39.6% bracket, which is so high that they probably would have been better off just leaving the money as a pre-tax IRA and spending it in the future at a lower rate. A partial Roth conversion, on the other hand, allows the couple to create just enough income to be subject to the lower tax brackets, while stopping before they reach the upper brackets.

Example 2: Continuing the prior example, Jeremy and Linda could convert as much as $14,900 and still remain within the 15% tax bracket (

The end result of the strategy is that the couple can convert exactly enough to ensure that their IRA is subject to the lower tax brackets today, but only those lower and more favorable tax rates. Of course, given that there's only so much room to convert until the higher brackets are reached, this means the bulk of the couple's IRA may remain in pre-tax form. Yet given a multi-year – or even a multi-decade – time horizon before they need to spend/use all the money, this isn't necessarily a problem. It simply means the couple will repeat the partial Roth conversion systematically each year in the future as well, continuing to whittle down the size of the pre-tax IRA (and grow the size of the Roth IRA), while ensuring each year that the conversions are modest enough to avoid ever hitting the top tax brackets.

Ultimately, then, the goal of partial Roth conversions is to find a balance, where the converted amount is low enough to avoid top tax rates today, but not so little that the remaining retirement account balance plus compounding growth causes it to be exposed to top tax brackets in the future, either.

IDENTIFYING OPPORTUNITIES

Clearly, one challenge to the strategy of Roth conversions is that the benefits are highly dependent on what future marginal tax rates turn out to be, in a world where we don't necessarily know that outcome for certain as of today. Projecting future wealth and known future income streams can be

Nonetheless, we can know

For instance, if someone experiences a layoff that leaves them without employment income for most of the year, his/her tax bracket may be just 10% or 15%, a rate that's hard to beat in any foreseeable future as long as there's any income tax system. In the extreme, if deductible household expenditures (e.g., property taxes, charitable giving, the

Similarly, a business owner that experiences a significant (pass-through and otherwise deductible) business loss might have an 'unusually low' income year where a partial Roth conversion can benefit at the low rate. Alternatively, a household that has an unusually large amount of deductions (e.g., for a significant charitable contribution, or perhaps paying a large outstanding state tax liability balance from the prior year?). And notably, because deductions are applied against ordinary income first and capital gains second, someone with high total income due to capital gains could still be eligible for low tax rates on a partial Roth conversion (although

REPTITION

For those transitioning into retirement, the years after wages and employment income end, but before Required Minimum Distribution (RMD) obligations kick in, can also be especially appealing for timing partial Roth conversions. For instance, a retiree in their early 60s might do a partial Roth conversion each year throughout their 60s, whittling down the size of a pre-tax IRA over time, such that by the time RMDs actually begin at age 70 ½, there isn't much of a pre-tax IRA left.

Example 3: Betsy is a single 60-year-old female who recently retired with a $20,000/year Social Security survivorship payment and a $40,000/year survivorship pension from her deceased husband. Betsy also has a $200,000 brokerage account, and a substantial $700,000 IRA (the combined value of her original IRA, and a spousal rollover from her deceased husband's 401(k)). In a decade when her RMDs begin, Betsy will face RMDs of upwards of $50,000/year (with an 8% growth rate in the IRA between now and then), propelling her into the 28% tax bracket even after her moderate deductions; by her 80s, the RMDs are projected to be more than $100,000/year, topping out the 28% rate and approaching the 33% bracket.

To manage the exposure, Betsy decides to do a partial Roth conversion of $40,000 each year for the next 10 years, which after her deductions just barely fills up her current 25% tax bracket, but stops short of the 28% tax rate. Repeated each year, this gives Betsy the opportunity to significantly whittle down her overall IRA exposure; in fact at this pace, her pre-tax IRA will still only be about $900,000 by the time her RMDs begin, which will produce RMDs of barely $35,000, allowing her to remain in the 25% tax bracket. In the meantime, Betsy will have accumulated a tax-free Roth IRA projected to have grown over $700,000 by age 70 ½.

The end result – by doing systematic partial Roth conversions for several years in a row, it's possible to remain in (and fully utilize) the lower tax brackets, while avoiding higher tax rates today, and whittling down pre-tax retirement accounts to the point that RMDs won't be subject to higher tax rates in the future, either.

HARVESTING INCOME The key aspect of the systematic partial Roth conversion is that deferring "too much" income – by accumulating and compounding an IRA and never withdrawing or converting it – drives someone into top tax brackets, and there's no way to go back after the fact and use lower tax brackets that may have been available in prior years. In essence, a low tax bracket available today is "lost" forever if not actually used in the current tax year. Which means for those who are already facing top tax rates, it makes sense to defer or avoid income, but

And notably, since the opportunity to fill low tax brackets is a "use it or lose it" scenario – because taxable events must actually occur in the current tax year to count in those income buckets – December 31st becomes a firm deadline for any annual low-tax-bucket-filling strategies.

Unfortunately, deciding how much income to create before the end of the year can be challenging, because sometimes you don't know what income (and deductions) will end out being until the very end of the year, leaving little or no time to do the calculations and the 'last minute' conversion.

In this regard, the particular strategy of doing Roth conversions with a planned recharacterization becomes appealing. Because

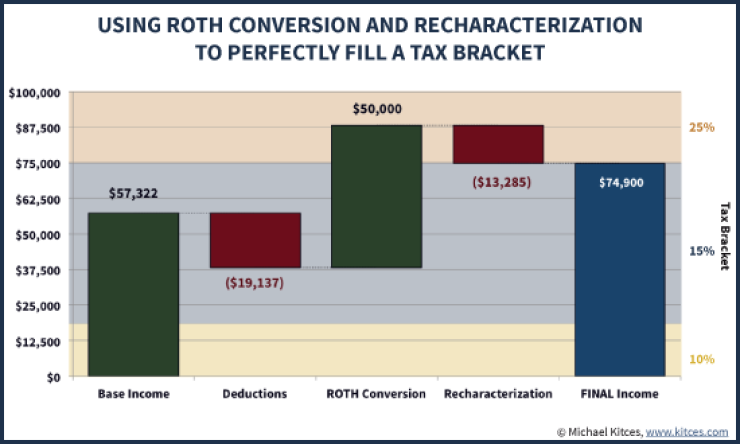

Example 4: Donald and Donna are retired and have approximately $50,000 of current income and $15,000 of deductions, and want to do a Roth conversion to fill their 15% tax bracket (

To avoid the risk that the distributions will be small enough to allow room for a Roth conversion but come so late in the year there's no time to do one, Donald and Donna do a partial Roth conversion, now, of $50,000, which would be sufficient to fill their 15% tax bracket even if total distributions from their investments turn out to be $0.

After the close of the tax year, it turns out that Donald and Donna have total income of exactly $57,322 and total deductions of $19,137. Their taxable income is $38,185, which means they could have converted exactly $36,715 of their IRA and still remained within the 15% tax bracket. Accordingly, they recharacterize $13,285 of their $50,000 Roth conversion (

The end result of this strategy is that even in situations where there is uncertainty about exactly how much to convert, the precise amount of the desired partial Roth conversion can still be accomplished, by converting more than enough up front, and then recharacterizing the excess afterwards. Or

CAREFUL EVALUATION

Of course, the caveat to all of this is that it's still necessary to determine the ideal tax bracket, or amount of income, to partially convert to a Roth in the first place. Ultimately, this is driven not only by

It's also important to recognize and remember that Roth conversions will themselves impact future tax rates, as the diminishment of a pre-tax IRA reduces future tax exposure. For IRA accounts that are projected to be large – where RMDs can propel the IRA owner into the top tax brackets – a partial Roth conversion is appealing to benefit from lower tax brackets today and avoid the higher ones in the future. But notably, if the entire IRA is converted to a Roth, it eliminates all future tax exposure, which means the future marginal tax rate may become so low that the last IRA dollars weren't going to be taxable anyway. In other words, the greater the (partial) Roth conversion, the less need there is to convert the remainder.

The bottom line, though, is simply this: the availability of low tax brackets is an opportunity that should be utilized before it is lost, and the partial Roth conversion (or a Roth conversion followed by a partial recharacterization) is a flexible strategy to ensure that those low tax rate buckets never go to waste.

So what do you think? Do you engage in partial Roth conversion strategies systematically with your clients every year? How do you figure out the amount to convert each year?

Michael Kitces, CFP, is a Financial Planning contributing writer and a partner and director of research at